Landing in my birthplace always gives me the feeling of a tired child resting his head in his mother’s lap, the comfort that says I’m home. This time, the feeling was warmer, for I had brought with me the joy of my son’s wedding to share with my family and friends. It felt like returning to a celebration.

But joy in this country is always fragile, more so in the border regions.

The minute I touched down in Islamabad, news broke of yet another suicide attack — 12 killed, dozens injured. The headline cut through my heart before I even reached baggage claim. Still, I drove to Peshawar, to my roots. To the soil that has always known both happiness and heartbreak.

When I reached home, the air was the same as when I left it. Dry, warm, filled with the scent of dust and bright sunshine. Children I once saw in school uniforms are now married. Cousins have grey hair. New faces sit where elders once did. But the streets have grown crowded, the tolerance thinner, the city restless. Yet, every corner still tells a story of life, and survival. And the unbreakable stubbornness of its people.

A native returns to his home in what was once known as the ‘City of Flowers’ and tries to make sense of its slow erosion, over decades, of culture, tolerance and joy. Where the city once pulsed with music, cinema, dance, poetry and coexistence, it struggles today under the weight of fear, radicalisation and silence. Is the old Peshawar just destined to exist only in his memory?

THE CITY THAT WAS

Forty years ago, Peshawar was one of the most vibrant cultural cities in South Asia. What Paris had in sophistication, what New York had in artistic energy, my city had in its own distinct, confident way.

I still remember my teenage days in a small village near Peshawar in the early 1980s. Back then, the city was alive with colour and melody, cinemas showing Pashto, Urdu, English and Punjabi films, the sound of the rabab floating through Dabgari Bazaar, and wedding nights throbbing with dance, drums and currency notes being showered over performers. Peshawar was a city of art, of scandal, of tradition and temptation.

There were musicians’ streets, poetry festivals, bookshops and open-air performances that carried on late into the night. In the Saddar neighbourhood, Khyber Café served as the informal headquarters of Pakistan Television’s Peshawar Centre, where actors, poets, writers and producers gathered daily. A short walk away stood Saint John’s and Saint Cathedral churches, and beside them the historic Jamia Darvesh Mosque. A coexistence of faiths carved naturally into the city’s landscape.

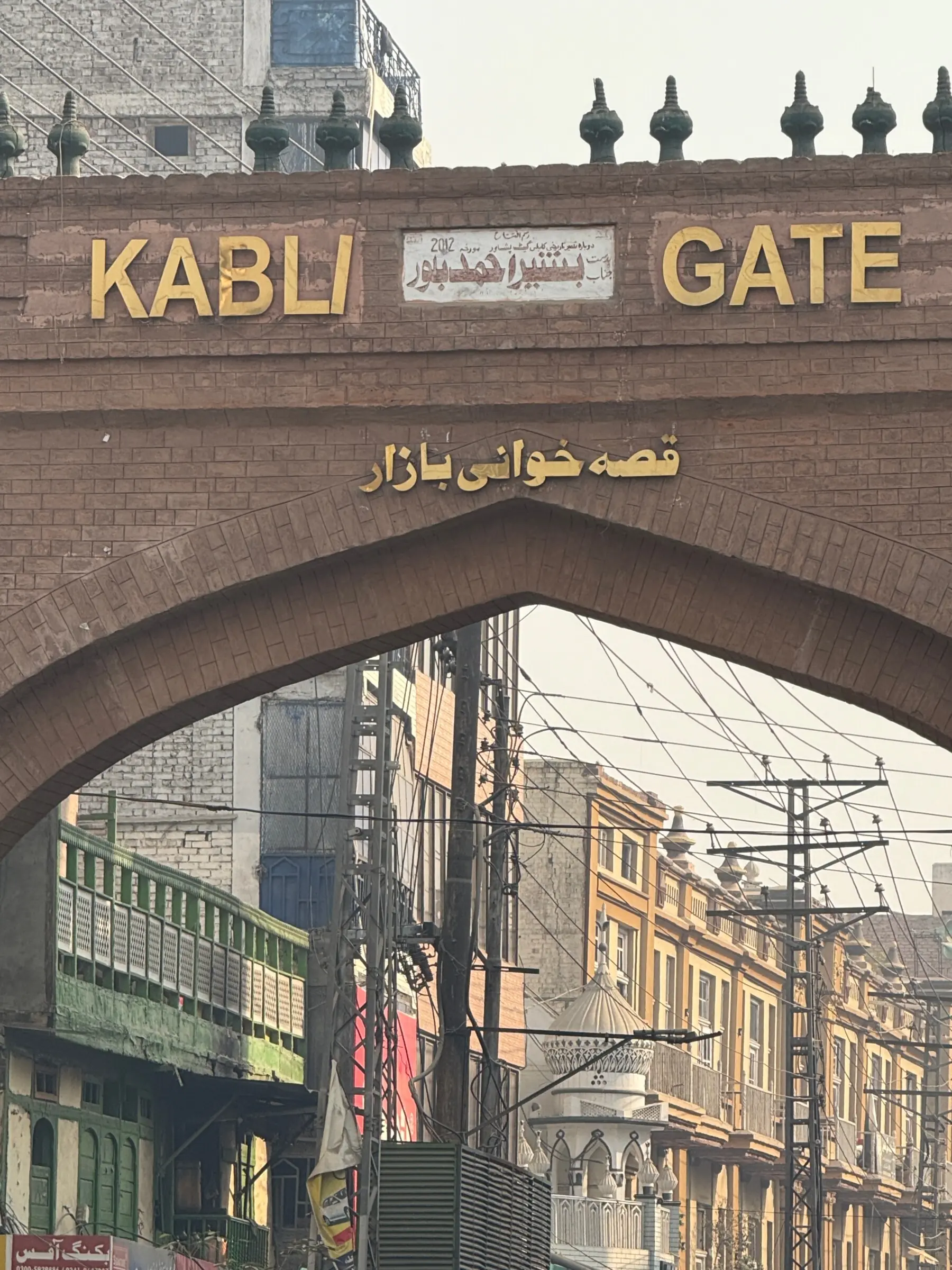

In Kali Bari street, Muslim, Hindu and Christian families lived side-by-side in a harmony that felt permanent. Every year, the month-long Jashn-i-Khyber festival filled the night air with announcements and music from Peshawar Stadium’s loudspeakers. And in Dabgari Chowk, the celebrated Pashto ghazal singer Khyal Muhammad would perform all night in the middle of the road, surrounded by people who came for poetry, not politics.

That was the Peshawar I grew up in: confident, open, generous.

THE TRANSFORMATION

But then came the Afghan war and Gen Ziaul Haq’s call for ‘jihad’. Overnight, Peshawar became the frontline of a global game. It turned into a Kalashnikov capital, a smuggler’s paradise, a city of spies and sudden millionaires. To own a gun was to be powerful, to fire it in the air was to be feared.

Over decades, religious seminaries multiplied, public art vanished and cultural spaces disappeared or were muted. Suspicion replaced neighbourliness. Extremism was not an accident, it was a slow, deliberate recalibration of society, one that suffocated the city’s cultural lungs.

On my second day in the city, I photographed a young Islamist student wrapped in a white turban, wearing a light-brown Schott NYC US Army jacket. The irony hit me like a flash: an American brand on a madrassa [seminary] student. When I asked about it, he smiled and said it was his “trophy”. I didn’t ask more. He happily posed for a picture.

That single moment pulled me 30 years back, to 1996, when the Taliban had just taken control of Afghanistan. Back then, they walked freely in Peshawar’s streets. The city was their resting ground, their moral laboratory.

And here I was again, 30 years later — the same story, the same spirit, just new clothes and a different brand. I didn’t ask this young man about his ‘trophy’. Not because I was afraid, but because I understood that, in our land, questions can sometimes be louder than answers.

History in this part of the world never moves forward — it keeps circling, dressing old beliefs in new symbols.

A WALK ON CINEMA ROAD

The afternoon light falls softly on Cinema Road, the street that once carried the heartbeat of the city. The air still smells of dust, tea and faint memories of songs that used to spill from cassette shops. My steps now echo where music once lived.

Inside a narrow tea shop, Jan Muhammad sits cross-legged beside his brass samovar. This was once the German Tea Shop, now everyone calls it Jan Muhammad Chai Khana. He pours boiling milk into cups, the sound of hissing steam blending with the low hum of conversation. He looks up and says, “Alhamdulillah [Praise be to Allah], the bazar is clean now, no obscenity, only business.”

The clang of kettles and the breath of steam are all that remain from a time when this road was alive with sound, posters and film lights.

There was a time when Cinema Road glowed every evening. Three proud cinema halls stood shoulder-to-shoulder: Picture House, Novelty and Tasweer Mahal. People knew them not by their official names but by what they looked like: Picture House was Makhamkh Cinema, the one in the front; Novelty was Manz Cinema, the middle one; and Tasweer Mahal was Pehla Cinema, the first one in the row.

Crowds of young men filled the street. Truck drivers, students and visitors from the villages of Khyber, Charsadda, Mardan and Kohat. They came for the films, for the laughter, for the noise that made this road feel like a fair. Music shops lined both sides: Sherbaz Khan Music Centre, Shalimar and Gul Sattar Khan. Their cassette racks glimmered under yellow bulbs, filled with Pashto, Indian, Persian and English songs. The road itself throbbed like a radio tuned between worlds.

The photo studios were tiny rooms where magic happened. A young man could pose and see himself printed beside Badar Munir, Musarrat Shaheen, Yasmin Khan or Suraya Khan — a small miracle made with scissors, negatives and glue. He would take that photo back to his hujra [communal space], proud and smiling, showing it as proof that he had met fame.

Now those same shops sell PVC boards and stationery — the film stars are gone, but the cracked walls still remember them. And through Photoshopping now, young men opt to be transformed into images of militants, guns in hand and a rocket-launcher on the shoulder.

A little ahead, the Tasweer Mahal lies buried under a 13-storey plaza. Novelty and Picture House have also been erased, bulldozed like memories no one asked to keep. Dust has replaced the crowd clamouring at the cinema gate, eager to get in. Only silence stands where the hero once leapt across the screen amidst applause from cine-goers.

Further down stands the Aina Cinema, its doors half-open to… whom? The ‘Ladies Gate’ sign still hangs above the narrow staircase.

The ‘Pay Box’ lettering survives, though a car now blocks the view. And above, the mural of dancers and musicians — colours faded — still hangs on through the years. This hall once echoed with clapping hands and Pashto film dialogue. Now it rents its floor to cars.

No one I ask says they miss those days. Maybe they have forgotten, maybe forgetting is easier. But for those who grew up in that sound and smoke, the loss runs deep — not just of cinemas, but of openness.

There was a balance once. Faith and fun walking side by side. Falak Sair and Capital Cinemas in Saddar, the Takhtu Jumat mosque between them, Blue Bells Music Centre beside. Naz Cinema near Masjid Mahabat Khan and Cinema Road itself beside Madani Masjid of Namak Mandi. After Friday prayers, some men went to the cinema, some to Dabgari Bazar — both part of one rhythm that made the city move.

Evening falls again on Cinema Road. At Jan Muhammad’s shop, the kettles cool slowly and the tea tastes like nostalgia — thick, sweet and a little burnt. The steam curls upward like the city’s last song. The walls are cleaner now but quieter. We have built plazas and lost poetry, scrubbed away the music but not the memory.

A CITY THAT WALKS THROUGH SMOKE

The morning sun in Peshawar was pale and kind. And then, that morning, a car bomb. A suicide attacker struck right in front of the Federal Constabulary (FC) Headquarters — formerly the Frontier Constabulary — in the heart of Saddar.

The blast ripped through the stillness of an ordinary workday. A white Suzuki, packed with explosives, rammed the gate before a suicide bomber detonated himself. Within seconds, concrete dust, smoke and fear clouded the street. The echoes rolled beneath the overhead BRT [Bus Rapid Transit] track, bouncing between the concrete pillars that now bear the stains of shrapnel.

Three FC personnel were martyred on the spot, several others were wounded. Under the overhead bridge, men gathered in silence. Children clutched schoolbags. Bikers slowed to watch the police lift the burned car with a forklift, its tires dangling mid-air. A haunting image of another day gone wrong. Nearby, an FC soldier stood guard over a blood-soaked shroud, staring at what little was left of the attacker.

And yet, just a few hundred meters away, life went on. Shops re-opened, schools and offices stayed functional, and traffic crawled as usual. The people of Peshawar, hardened by decades of violence, carried on with that familiar numbness that only a city long at war can understand.

By noon, the road was cleared. The glass shards on the asphalt shimmered like tiny memorials in the sunlight. For outsiders, it was a terror attack — for Peshawar, it was Monday.

WALTZING WITH TERROR

This November, when my son was getting married in New York, my sisters in Peshawar insisted to have a traditional nakreezy — a henna night with music and dance — in my hometown. They wanted a Pashto singer, someone whose voice could bring back even a trace of the old Peshawar. Our friend, the renowned Pashto singer Sarfaraz Afridi, offered to perform along with his young son, Arman Faraz.

I wanted to host them on a stage worthy of artists, decorated with candles and roses. The way Peshawar once honoured its musicians. I visited 17 wedding halls. Everyone refused. “No live music,” they said. “It is a sin.” As if joy itself had become forbidden. As if melody threatened the order of things.

So I built my own stage. On the rooftop of our four-storey family home, in the heart of our village, we placed speakers on all four sides. Not to provoke anyone, but to remind them of what had been forgotten. Sarfaraz and Arman performed until dawn. Their voices floated over our neighbourhood like a small rebellion.

That night was my protest. My refusal to accept silence as the new normal.

For the main wedding, I had invited a Khattak dance troupe, a symbol of Pakhtun identity and pride. The FC, whose dancers I had invited, was burying its own after the bomb attack. I assumed the performance would be cancelled. But on the wedding day, the troupe arrived. Still grieving. Still shaken. But determined.

Their presence was more than entertainment — it was a declaration. A refusal to let terror dictate how people live, celebrate or express their culture. In front of 1,000 guests, their dance was a quiet but unmistakable act of defiance.

For a brief moment, I saw my old Peshawar again.

THE UNHEARD SONGS

In my father’s youth, in the 1960s, things were different. He told me that when women dancers were invited to weddings, they would first go to the women’s side of the house. Female hosts would welcome them with tea, speak kindly and drape a chador over their shoulders. A gesture of respect, of protection. Only then would the dancers step toward the hujra, escorted by male elders of the family.

Before the music began, an elder would raise his hand and declare: “She is our guest. She has come to bring joy to our celebration. Respect her as you would respect your own daughter.” Those few words were like a royal decree, an invisible shield. No one dared misbehave, no one dared touch. That was Pashtunwali — the old code of honour that balanced pride with protection.

I grew up in the early 1980s, when the night air smelled of kerosene lamps in my village. In our villages, there was no cinema, no television, no theatre. Only the female dance party in the hujra. The night would go on — currency notes showered upon the dancers, tossed over the groom and his friends, laughter mixing with the music. The mehfil glowed until midnight, when it ended with bursts of gunfire in the air, a final announcement to the surrounding villages that the dance was over. Yet, within that fiery, fraught atmosphere, the dancing girls somehow felt safe.

They came from everywhere — from Swat’s Banr Bazaar, from Mardan, from Rawalpindi, sometimes from Lahore or from Dabgari Bazaar itself, the old red-light heart of Peshawar. Names whispered in gossip and admiration: Shamshad Begum known as Shamshado, Farzana, Shahnaz, Babli, Chanoo. Women who carried the rhythm of a culture and the shame of a society that refused to own them.

But that balance has been shattered. First by the Kalashnikov culture of the 1980s, then by the militancy and false piety that followed. The same land that once danced to the rabab began to tremble under sermons and gunfire. The same people who clapped to melodies now judge with verses.

Today, a woman with a song is a threat. A woman who dances is fair game for anyone’s bullet. Her name was Muniba Shah. A name that most of Peshawar didn’t know until it was followed by the phrase “shot dead.” She was a damma, a Pakhtun dancer, an artist, a survivor of a cruel tradition that praises art but punishes the artist. She danced her last dance in the City of Flowers.

No protest. No statement. No civil society outrage. Only a few blurred photos on social media, her painted face frozen mid-smile… and a city moving on as if nothing had happened.

Muniba Shah is not the first. She joins a silent chorus: Shabana, the dancer from Swat, shot dead in 2009, her body dumped in a public square. Ayman Udas, singer and TV performer, murdered by her brothers for “dishonour”. Ghazala Javed, the nightingale of Peshawar, gunned down with her father in 2012. Sumbul, Sonia, Resham, Lubna, Khushboo — each killed for saying no, for performing, for living.

Eighteen names that are known. Countless others lost. No monuments. No memorials. No justice. Just Facebook comments asking what she wore, what she did, as if death needed justification. But if music is our soul, why do we keep killing our singers? We praise God for beauty but destroy the ones who carry it in their bones.

Muniba Shah will not perform again. Her anklets lie still, her music cut short. Somewhere tonight, another girl in Banr Bazaar may look at her picture and feel both wonder and warning — dreaming of the stage, fearing its price.

THE HIGH AND THE LOW

He was known in our streets as “Nasimy”. His real name was Nasim Maseeh, but names fade fast in the dust of forgotten lives. He was the man with the broom — a long jharroo in one hand, a small steel cart in the other — walking through Nothia Jadeed, Miskeen Abad, Judge Bungalow and Kotla Mohsin Khan every dawn.

A faded Palestinian-style scarf tied around his head, dark skin shining with sweat, white teeth flashing when he laughed. A laughter full of life and, at times, full of quiet sorrow. After sweeping, he would sit cross-legged on the ground, cracking jokes, calling out to the housewives in his broken Pashto: “Ay baaji, chai milay gi? Ay mory, aik paratha mere liye bhi! [Sister, can I get a cup of tea? One paratha for me too!]

Every woman in the neighbourhood knew him, respected him. And he, in return, respected everyone. Working and smiling, never demanding more than a greeting or a cup of tea.

But when someone threw waste food, plastic or burned trash on the same street he had just cleaned, Nasimy would laugh again. A deep, tired, saddened laugh, the kind that hides pain behind politeness.

A few days ago, I learned that Nasimy had died. Inside a blocked gutter at Darul Uloom Usmania, the very madrassa whose drains he was cleaning. He suffocated there, in the dark, doing the work no one else wanted to do. He died where the city’s conscience never dares to go.

I asked around: was he married? Did he have children, a home, a family? No one knew. There are thousands like Nasimy in Pakistan — most belonging to Christian and Hindu minorities, living without contracts, safety or respect. They clean the mess of millions, yet die in silence.

Sometimes I think we Pakhtuns, indeed the entire Pakistani nation, are among the most contradictory of people, with arrogance born out of the caste system. Those who cut our hair and make us beautiful, we call nai, implying a lowly status. Those who shape the clay into pots that feed us, we call kolal, equally lowly. Those who bring colour to our lives, we still treat as low.

We are blind to the truth that they — not us — keep the rhythm of life alive.

FROM KALASHNIKOVS TO TIKTOK

Forty-five years later, the story has not changed, only the platforms have. From Iqbaly and Dabangy to Tila Khan, Ayuby and Papu, these names ruled the underworld. They were legends of ‘badmaashi’ — gangsters, assassins, drug lords — until SSP (Senior Superintendent of Police) Sifwat Ghayur arrived with an iron will. One by one, his team took down the city’s crime lords. But in a cruel irony of fate, SSP Ghayur and his men would later be killed by the Taliban they once fought to contain.

The gangsters of Peshawar are no longer hiding in dark alleys; they are performing on TikTok. They threaten, boast and mock each other in viral videos, before ending up dead in police encounters that everyone knows are paid for.

Just a few days ago, Malik Adam Khan, an Afghan-Pakistani figure once feared, was killed along with his companions. Rumours spread across the city that his rivals, Mumtazy “Two Feet”, Haji Habib and Breet Khan, paid the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa police for the ‘operation’. Hours later, Mumtazy threw a celebration, a night of dance and gunfire, mocking the death of his rival.

In the 1980s, Peshawar’s poison was heroin and opium — today it’s ice, crystal meth, a drug that burns young minds faster than war ever did. The city’s streets are no longer full of storytellers or musicians — they’re full of dealers, addicts and a lost generation.

And then, the ultimate tragedy. Videos surface of fathers selling their own children for food. Crying boys and girls under the age of 12, auctioned in shame because poverty has crushed the last pillars of Pakhtun honour. It was unthinkable once. It’s the reality now.

Guns, drugs, gangs and tears — the story repeats itself. But somewhere between the smoke of the Kalashnikov and the glow of a TikTok screen, the soul of Peshawar burns among its ashes.

WHAT REMAINS

I often say I lost my city. In many ways, I have. The Peshawar of my youth — diverse, artistic, tolerant — survives now only in memory and in scattered pockets of resistance.

But I also know this: culture is resilient. Music finds cracks to slip through. Joy returns in unexpected places. It does sometimes on rooftops, sometimes on a wedding stage trembling after an attack. The extremists took much from Peshawar. But they have not taken its soul entirely. Not yet.

I carry that belief like I carry an old photograph — edges fading, centre glowing. And I hold on to it, because cities don’t die when buildings fall or when cultures are silenced. They die when their people stop remembering what they once were.

Until then, every Pakhtun must ask: what kind of flower garden are we, if we keep watering the soil with the blood of our own roses?

Majeed Babar is a writer, broadcaster and photojournalist with over three decades of reporting experience across Pakistan, Afghanistan, the United States, Europe and Central Asia. His work has appeared in The New York Times, RFE/RL, Le Monde, ABC TV and the Chicago Tribune. He currently divides his time between Prague and New York, focusing on documentaries and investigative storytelling

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 4th, 2026

Header image: One of the country’s most vibrant annual cultural festivals, Jashn-i-Khyber (as seen above during the 1990s), drew artists, poets, traders and performers from across the country for a month-long celebration of art and economy. Dancers and musicians from the Frontier Corps and police constabulary welcomed participants at the Peshawar Railway Station and public venues, transforming the city into a living stage of shared heritage and cultural pride. — Author